Thoughts Before Diving In

So we pulled out another blues genre!

How will this one be different from the last? Wildly, we assume. What do you think of when you consider Louisiana music? Zydeco? We did. Will these blues have strong zydeco, Cajun, and French influences? Louisiana already seems like a diverse musical location when you include jazz and festival music. We also assume it’s all going to have great tempo for dancing. And, honestly, the swamp blues sounds uncomfortable, humid, and thick. We’ll see.

History

While our last genre, Piedmont blues, was wrapping up around WWII, Louisiana blues was coming into its own at the same time. There’s an audible distinction to be made between pre-war blues and post-. This is due to two major game-changers: the popularity of the electric guitar and the development of the interstate highway system.

Prior to the war, the Louisiana blues was more akin to the country blues or Delta blues, but with a twist of that unique Cajun and Creole influence–terms we’ll expand on in a minute. The guitar was the centerpiece, and though a small band of other instruments was present, the sound was folksy and basic (we mean that in the best of ways). After the war, however, electric guitars were beginning to be used all over the U.S., and with them came more layers and variety of sound, amplifying the energy of the blues and elevating it as a genre. If we wanted to be really presumptuous, we’d say that rock and roll as we know it owes its existence to this moment in blues history.

Around the same time, highways were being developed, connecting Louisiana with Texas and eventually the rest of the nation, giving musicians the opportunity to tour and bring back to Louisiana the sounds of their neighbors and other major cities. For example, just listen to the similarities in sound between Louisiana blues and the Texas honky-tonk and dancehall music.

The Basics

Louisiana is an absolutely crucial location in the evolution of American music. It is the cradle of jazz, Creole, zydeco, and Cajun music. So, naturally, this blues genre is very diverse, making it difficult to distinguish a single audible theme. And to further complicate things, Louisiana blues is typically divided into two major categories: New Orleans blues and swamp blues. That being said, we learned many of these artists don’t fully commit to either; they tend to dip their toes in multiple forms of Louisiana blues.

Before diving into each genre respectively, we noticed some similarities between them. Since the 50s, both almost always feature electric guitar, making this a perfect compliment to Piedmont’s exclusively acoustic narrative (see our blog post: Blues Part 1). Both styles are typically meant for dancing, because of their shared history. Both often feature full bands, which is a big departure from blues commonly heard elsewhere in the early half of the twentieth century. But if you hear an accordion, be wary–you may have stepped in some zydeco.

New Orleans Blues

With NOLA blues you can definitely hear jazz and Caribbean influence. It’s a faster tempo, with lots of piano and horn to jam to. These guys often have more of a band, including percussion and accordion. This is the club music of the genre. Here are some examples from our playlist:

“Those Lonely, Lonely Nights” – Earl King

“Some Day Baby” – Lonnie Johnson

“Tipitina” – Professor Longhair

Swamp Blues

This subcategory can have a slower tempo, although it’s often compared to zydeco and Cajun music. Its minimalism lets its folk roots shine. It’s heavy on the harmonica and light on the percussion. The percussion commonly includes the washboard or rub vest.

A note on the nebulous origin of the term “Swamp Blues” from Joyce Jackson, essayist at Louisianafolklife.org:

Exactly when the term originated is unclear, but there exist several origin narratives. Silas Hogan, who was eighty years old at the time of this interview and was the oldest active bluesman in Baton Rouge, claimed that it refers to the Devil’s Swamp, just on the edge of Scotlandville, where most of the bluesmen had lived for the past fifty years. He remembers how they would hold jam sessions on the porches of their homes, overlooking Devil’s Swamp. So the name ‘swamp blues’ seemed appropriate and the bluesmen started referring to their highly percussive sound as the ‘swamp sound.’

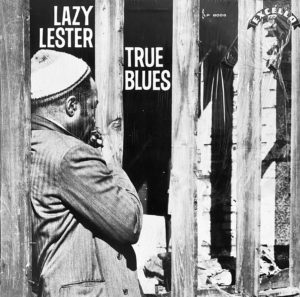

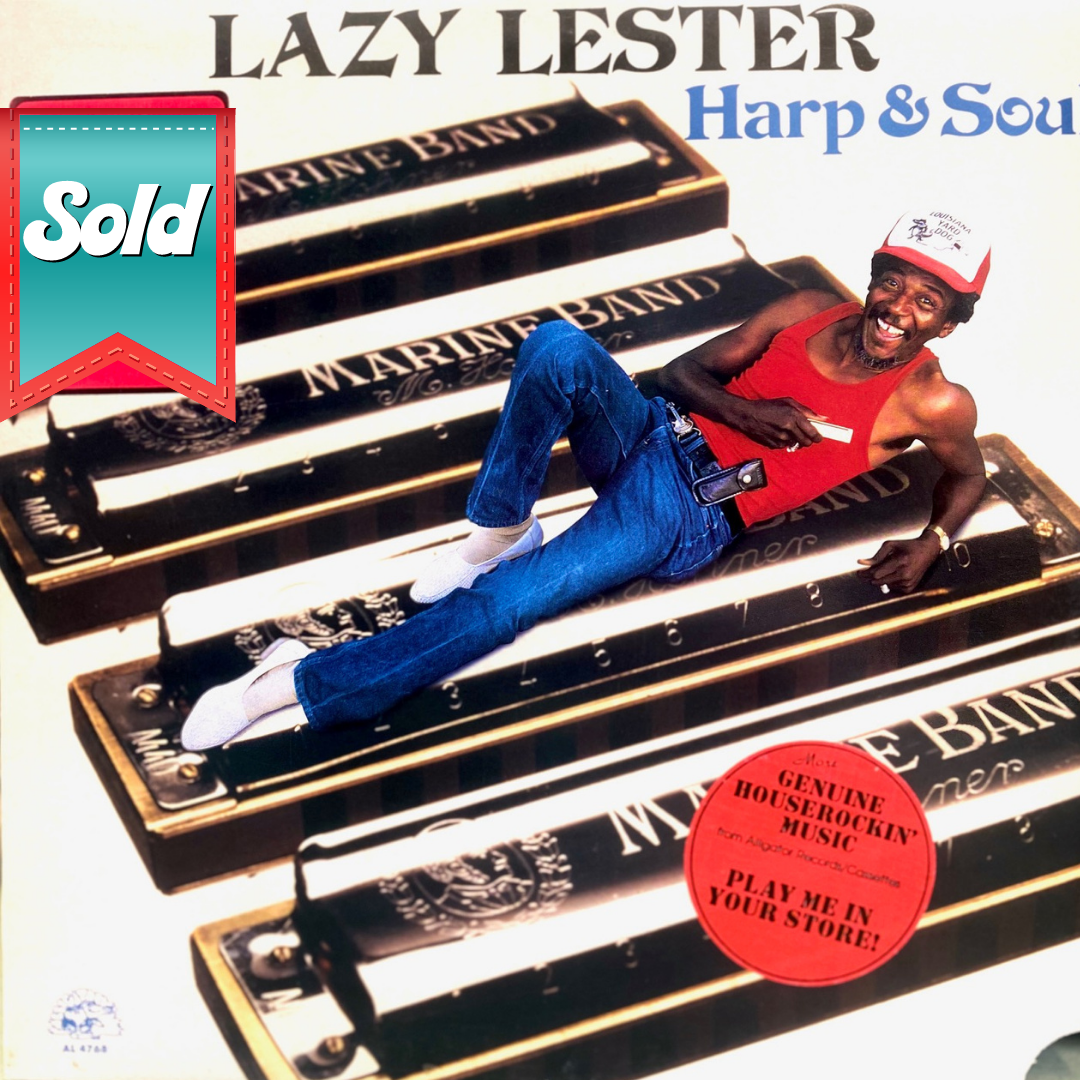

When I asked Lazy Lester about the designated swamp sound behind stage at the 2017 Baton Rouge Blues Festival, he replied:

“I was right there in [J. D.] Miller’s studio when we talked about trying to find a name for our sound. Miller said everybody in other regions have a name, Mississippi Delta sound, Piedmont sound, we also need to name our sound. So, we thought about the Louisiana swamps and we just started calling it the swamp sound right there in that studio.”

Interestingly, swamp blues seems like a detour for some artists. It became popular in the 1950s, had a short heyday, then lost popularity, and swerved back into zydeco around the 1970s. Also, if you want to make it in this game, change your name to “Slim.” It’s worked for many. Some examples:

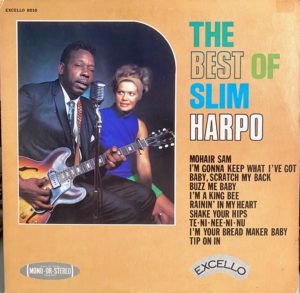

“Te Ni Nee Ni Nu” – Slim Harpo

“Saint James Infirmary” – Snooks Eaglin

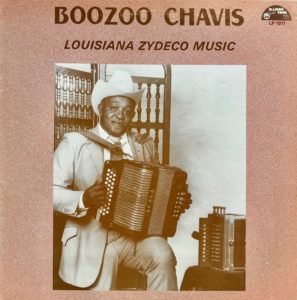

“Paper In My Shoe” – Boozoo Chavis

Back To The Basics

We couldn’t talk about this genre without mention of the 12 bar blues. It came up a lot in our limited research. This basic song structure is so prevalent in blues and rock that you probably recognize it without knowing it by name. Think of the driving guitar parts of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B Goode,” Buddy Holly’s “Rave On,” and Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll,” just to name a few. It was a popular song structure in the early days of electric Chicago blues, which is probably the most obvious outside influence on Louisiana blues. The new highway system being constructed in the late 50s allowed a lot of cross-pollination between the burgeoning Chicago blues scene and Louisiana blues, bringing the 12 bar structure to the South. For more technical understanding of that musical template, check out this tutorial on the PBS website:

This genre was really hard for us to learn to identify by sound. Louisiana blues is unique in that it wears all of its influences on its sleeve at once, making it difficult to narrow down who is what and what goes where. To better understand the boundaries of this genre we had to also learn a little bit about each of these influences. We appreciate the adjacent education we got about the difference between Cajun and Creole. We always welcome more schooling on the subject if we’ve stepped in it, or you have something personal and illuminating to add.

Cajun=Louisianians of Acadian (French-Canadian) descent who settled in (mostly) southern Louisiana. Cajun music includes some French and French-Canadian flavor and traditional structure(s).

Creole=A mixed ethnicity, distinct to Louisiana, of any races who were either native to the area or had settled in that area in the 1700’s and beyond. In short: Creole music is Louisiana folk music.

We also had to get a jump on researching zydeco, just to understand when we had crossed the border of the genre at hand. It’s still hard to hear the difference at times, and totally unnecessary, anyway, if you’re already vibing. We’ll cover zydeco more thoroughly another time, but it’s enough to say here that though zydeco contains blues as an ingredient, it is traditionally dance music with a blend of other Cajun and Creole sounds, meant for high-energy social gatherings.

We want to point out that there are artists born in Louisiana that we (and others, more esteemed) don’t consider Louisiana blues. Lead Belly and Buddy Guy, for example. And this genre has some additional crossover with genres we’ll cover later that are still in the genre jar, like Howler blues, zydeco, and R&B. Namely Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s “Ain’t Got No Home,” and Aaron Neville’s (equally amazing, but for totally different reasons) “Tell It Like It Is.” You may notice some heavy-hitters missing from the list of notable artists below. Stay cool–they’ll show up later in the blog.

Louisiana blues is a whole mood. Its call to get you moving makes it feel inappropriate to listen on a Spotify list. This sound is made for a live venue. It’s enough to make someone want to hop in a car for a road trip over to that boot state and hit some bars. But don’t right now. Wear your mask and stay home with this inappropriate Spotify list.

Pop Trivia

- Check out actor Hugh Laurie’s turn at playing “Louisiana Blues” (He’s British)

- We learned that the song “Susie Q” we’ve heard so many versions of started as a piece of Louisiana blues written and performed by Dale Hawkins

Notable People

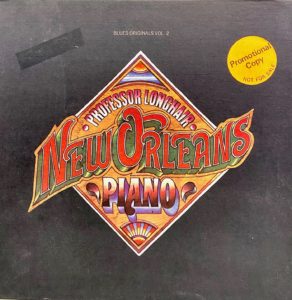

- Professor Longhair – Essential Louisiana music. The live version of “Tipitina” on our playlist is everything

- Guitar Slim – no relation

- Slim Harpo – no relation

- Lightnin’ Slim – no relation

- Marcia Ball – To our rookie ears, she belongs in the family tree of country/western, yet she showed up on nearly every list of LA blues musicians

- Lazy Lester – According to him, he ain’t lazy; God knows he’s just tired!

- Clarence Garlow – We love “Bon Ton Roulay”

- Boozoo chavis – Love the song “Paper In My Shoe”

- Katie Webster-We had a helluva time trying to find famous women in this genre! Webster was nearly the only one. !? We’re all ears if you readers know any

- Tuts Washington – Mostly a pianist, tap dancing on the brink of ragtime

- Smiley Lewis – Here we’re getting closer to a Chubby-Checker-style of rock and roll piano and brass

- Nathan Abshire – This fella can wail and jam an accordion like nobody’s bizz

- Champion Jack Dupree – Might have a problem

- Clarence Edwards

- Silas Hogan

- Lonesome Sundown – A nickname dreams are made of. Music’s good, too

- Louisiana Red

- Moses “Whispering” Smith – His voice is uh-mazing

- Smoky Babe – One of the artists closest to country blues we listened to in this genre

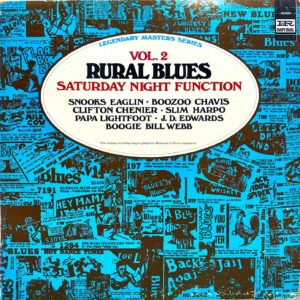

- Boogie Bill Webb

Examples

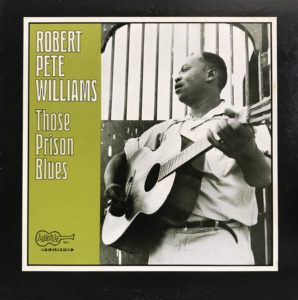

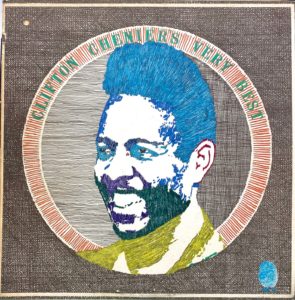

Check out some great examples of Louisiana blues that are currently in stock. Click on each image to see the album on our products page or in our Discogs Store. We have more selections of blues in on our shop page.

How Do Stephe and Wade Feel?

Stephe:

My Two(25 or maybe 50+…) Cents:

Much like Piedmont Blues, I feel like Louisiana/Swamp/New Orleans/Etc. blues is more of a style or a sound than a genre. The crossover between this style and jazz, zydeco, folk, and early rock and (or) roll further complicate my feelings. There is a sound and a feel to the music but, sadly, I am not feeling it as much as I was hoping. Snooks Eaglin is an all time favorite and I definitely dig songs by Slim Harpo, Smiley Lewis, Tuts Washington, Louisiana Red, Lazy Lester, and Clifton Chenier but I doubt I would spend a night on the porch dedicated to this genre. Also very sad for the lack of female representation.

Wade:

Unlike swamp coolers, which weirdly enough work better in drier climates, the swamp blues actually works in the swamp. Well, that’s what I’ve heard anyway. I feel like if someone was like, “I need the blues for this soundtrack,” they’d probably get some music here. I do really dig the diversity of sound and influences in the New Orleans blues though. Professor Longhair and his protégés have long been some of my faves. I feel like these genres are in the middle (geographically and evolutionary) of an ecosystem of other genres I like more (and will mostly be sticking to).

Pairings

Sweat, a crowded dancehall, worn boots, crawfish, shoe paper, swamp coolers, waking up alone

Favorites

Divisive genre! Each of us had a preference for a different sub-category. In the swamp arena: Snooks Eaglin was popular, Lightnin’ Slim, Lazy Lester, and that “Paper In My Shoe” by Boozoo Chavis’ll get in your head something terrible. In the New Orleans arena: “Bonton Roulet” by Clarence Garlow, “Finding My Way Back Home” by Buckwheat Zydeco, and the immortal Professor Longhair seems to embody all that is Louisiana music, so hats off to him.

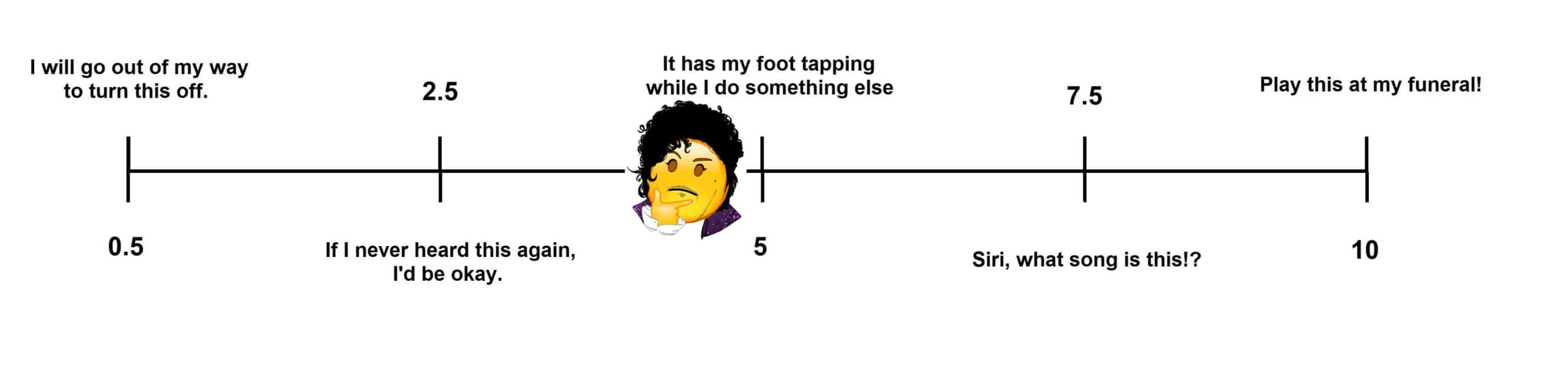

Princemometer

This got a 4.75. Some loved; some did not. The haters brought the average down to the low end:

Further Reading and Sources

http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/brblues1.html#tab11

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louisiana_blues

http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/treas_trad_la_music.html

Blog post’s featured image adapted from the album “Cajun and Swamp Pop Super Hits.” Artist–Mike Bordelon 1987

Come Back Next Time For

A shot of death and black Metal with a stoner and doom twist. Oh my!